Hi everyone!

I’m back! I’ve been crazy busy with a new freelance job, family health issues, and resuming my figure skating training.

Many of you may not realize I’m a figure and speed skater. After injury and equipment issues, I finally started skating again a little over a week ago.

Somehow, my overthinking has reduced, possibly because I’m distracted by breaking in new skates (they are STIFF, y’all).

This post is a bit of a departure from my usual content, but I wanted to share my strategies for dealing with overthinking since I know we all deal with it somehow.

Let me know what you think in the comments!

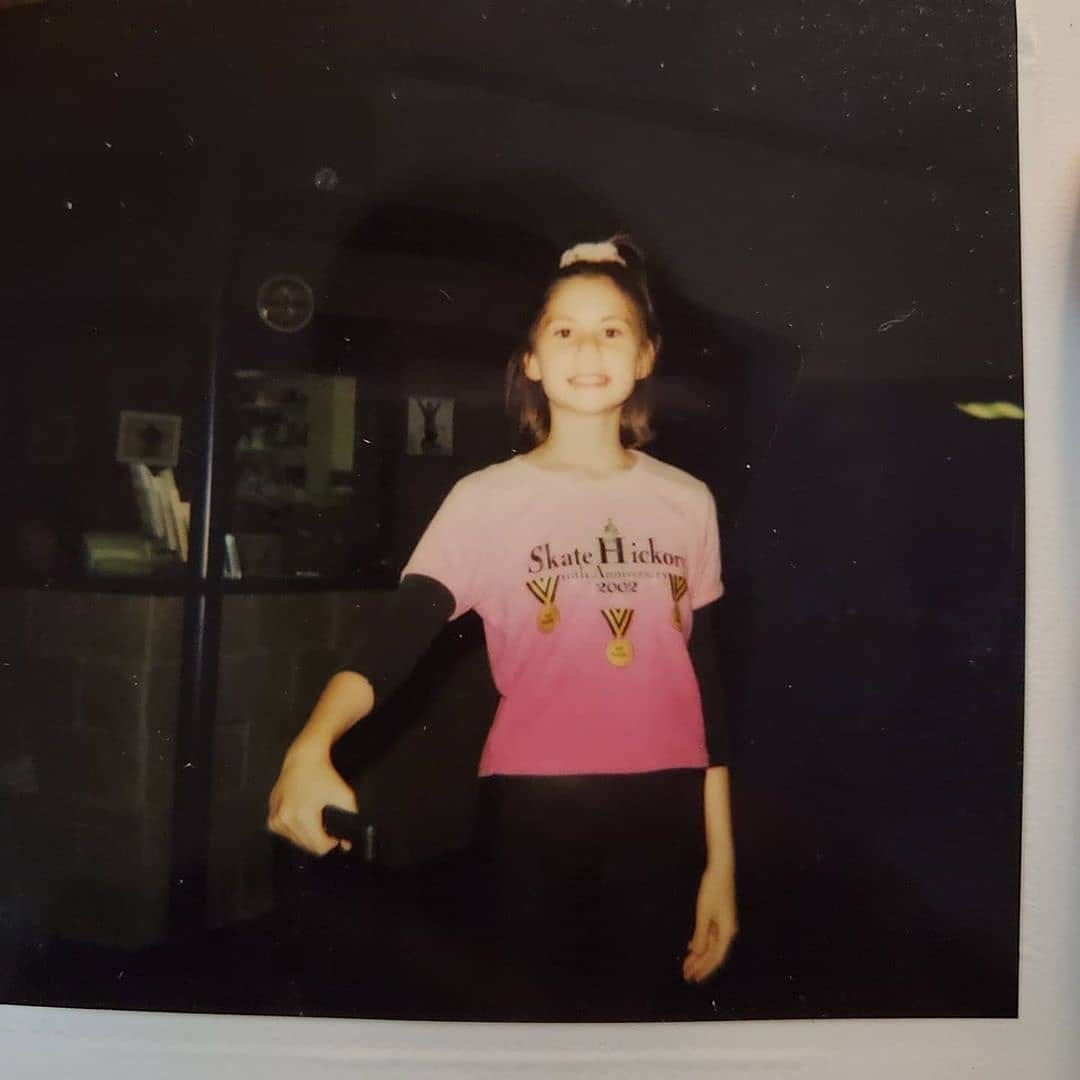

I’ve been figure skating for a quarter of a century. And I have been overthinking for almost that long. The jury’s still out as to what I’m better at, although I have a pretty good idea.

It all started when I was eight years old. I was told I couldn’t jump and was best suited to ice dancing.

I took what the coach said at face value and just stopped trying. Sure, I kept skating freestyle (jumping and spinning), but I lost belief in myself. I thought I was doomed — if that coach told me I couldn’t jump, why was I still trying?

When I was a bit older, another coach came to my rink. He didn’t tell me I couldn’t jump. Instead, he demanded I do a jump that I had been struggling with. My mom had taken me throughout the Tri-State area to different rinks to see coaches about landing this flip jump. All were unable to break through the mental block I had around it. This coach was different. He told me to “just do it” (he was Russian, and that was one of the few phrases he knew at the time). So I did.

Not only did I land the jump, but I could also land another jump that eluded me: the lutz. I realized that even though the coach was scary (or perhaps because of it), I got out of my way and pushed through the blockage.

After that, I started to believe in myself and started focusing. I began to believe in my ability to jump and spin. I also lost 30 pounds after finding out I had food allergies, changed my diet, and started having a better relationship with food.

I went from being a chubby girl told she couldn’t jump to being a teen athlete who was winning competitions.

Eventually, I started working with a strength and conditioning coach and became a better all-around athlete. I learned to speed skate (something previously held zero appeal) and found that it helped my figure skating, so it became a secondary sport in-season. I started biking. I became more adventurous and tried new things.

Throughout the years, I’ve had good experiences and less-than-ideal experiences with coaches.

The latter coaches, either through indifference or their own hangups, bashed my confidence into the ground. It was like being told I would never jump all over again.

One of these coaches tried to mold me into something I would never be: a skater in their image. I was told, subtly and directly, that who I was wasn’t good enough. I had to adhere entirely to their system. My skating technique was pulled apart and replaced by a very rigid technique in which moving slightly incorrectly was wrong. I was given specific training schedules that were planned down to the minute. We did performance run-throughs where every little thing I did wrong was picked apart; in a separate room after the performance, I was “judged,” and what little confidence I gained from the opportunity to perform for people was quickly eroded. I was taught to think a lot more than I probably had to think about technique, and I started overthinking my jump and spin technique, trying way too hard, and, more often than not, sabotaging myself. Then the coach would criticize, I would take the criticism to heart, and I would get even more “stuck in my head.”

I reasoned that I would finally do it perfectly if I could think through it.

That’s when the overthinking began in earnest, but I didn’t realize that until years later.

No matter how hard I tried, it still didn’t seem good enough to certain coaches. I overcompensated by overthinking, and skating became both exhausting and demoralizing.

Gradually, my love for skating started to fade.

I finally got nurturing coaches who believed in me throughout my late teens, but I still struggled to believe in myself. I stopped trying after the previous coach told me I was too much of an overachiever. I phoned it in more often than not because I was too afraid of “failing” and getting hurt even more.

Or, I went back into overthinking/overworking mode and burned myself out, then returned to putting in less effort. In both situations, I shut myself down to a degree. I tried to hide my light, my natural love for performance.

I thought if I could stay small, I could avoid being hurt.

I traveled to work with the coaches who trained me for my last qualifier, the Regional Championships, at age 18. I skated clean (staying on my feet and not making major mistakes), but I was disappointed that I didn’t make the final round, so I quit competing.

After my competitive career, I took lessons occasionally, but I was a lone wolf, just trying to maintain my skills on the ice. As I continued to skate solo, I became increasingly stuck in the same routines and, worse, stuck in my head.

Being your own coach is like trying to be your own therapist — you lack the objectivity to do it well, so instead of getting “better,” you’re usually running yourself in circles. Most of us need outside observers to guide us and redirect us when we get off the path.

I certainly did, but I convinced myself I didn’t.

The only times I seemed to shine on the ice were when performing.

Skating to certain songs that moved me, I allowed the music to flow through my body, and I somehow knew what to do. Sometimes, I improvised during a performance because that’s what the music called me to do.

Performing was when the overthinking quieted, and I could feel something like peace and get into a flow state.

I was focused on the music, the audience, and living in the moment.

Throughout my career, I’ve been told (by different people) that my skating moved them to tears. I still love skating because it’s a creative outlet, and I can touch people through my performances. It’s like my theatre, where I can tell a story through skating and make the audience feel. There’s no other feeling like it.

My special skill, other than my supposed ability to move people with my skating, is burrowing so far into my own mind that I talk myself out of things before I even try. But I’m working through it now.

In 2019, I worked semi-regularly with a few coaches and competed in an adult international competition. I did better than I thought I would, placing first in the artistic event and fourth in the freestyle event. I skated clean. I only tried jumps and spins in my comfort zone and skated to the best of my ability.

Most importantly, I had fun. At the artistic event, I felt a rush of joy just being on the ice. I hadn’t felt that way skating for at least a decade, especially not in a competitive context.

Somehow, I still felt like I wasn’t good enough. Although I received some positive feedback, I still looked at the other competitors and judged myself against them.

“They are stronger/thinner/better” than me, I would think, and I resolved to try to follow their path. If I could make myself into a copy of a “successful adult skater,” I could be worthy. I could go to Adult Nationals and win. I could go to International events and win. Then, I would fulfill my destiny.

I was all set to go to two such events when COVID happened. The events were canceled, the rinks were closed, and I stayed home. In those early quarantine days, I only walked, biked, ran, and took pictures.

Later, as things became slightly less apocalyptic, I took up roller skating on specialized figure skating-type skates and mastered an axel and a double salchow before the ice rink opened. My bravado energy was going full force.

“I’m going to go back and get super strong and get ready to compete”

That’s what I told myself. But I didn’t skate much.

I felt like I had lost much of that love and motivation for skating. If I could only get better, I would feel better, I thought. But that is backward.

You have to feel good about things before you “get better.” You have to accept where you are and then make considered changes to get where you need to be.

But what if “where you need to be” is based on flawed thinking?

I didn’t notice my overthinking or identify it as such until my coach pointed it out a few years ago.

I skated up to him after bombing another jump, explaining why I thought I was failing. He listened patiently, then showed me the video he had taken.

“There’s really nothing wrong with the jump, the jump is fine,” he said. “You’re just talking yourself out of it before you even try.”

Finally, all my troubles made sense.

My issues stemmed from overthinking, not a lack of potential or skill.

I’m already an anxious perfectionist with ADHD, but I realize that overthinking just neutralizes me.

Instead of making me more prepared for the jump and helping me “figure it out,” the process makes me more likely to fail.

Here’s how I stopped overthinking in its tracks (or ice patterns).

I rely on my coach’s judgment.

I thought it was a sign of rugged self-reliance to figure out exactly what I was doing wrong with my jump/spin/whatever and then share my observations with the coach. I thought I was being observant and intuitive and solving my only issues.

But in reality, I was usually overthinking and creating problems to solve when none existed.

So now, instead of coming to the coach and telling THEM what I was doing wrong, I would receive their feedback.

If they didn’t say something was wrong, it wasn’t. Everyone has different opinions, but constantly picking out nonexistent problems to resolve doesn’t help anyone.

I try to shut my conscious brain off

Not literally, of course — that would be impossible — but before I would go into jumps and spins, I would try to get all Zen instead of doing the usual overthinking bit.

Sometimes, I intentionally think of something else, like what I’ll have for dinner or what kind of caption I’ll put in my inevitable skating reel.

We usually need to think a lot less than we do, especially when it comes to things we already have in muscle memory.

Try less, not more

This ties into the one above. Have you ever had a moment when you realized that you are trying way too hard to do something you know you can do? It would be like thinking about how to breathe or how to tie your shoes. Some things just become a part of you after a while.

Simply put — you don’t really have to try so hard, you just think you do.

When you care about something, it’s natural to TRY SO HARD OH MY GOSH I HAVE TO DO THIS JUST PERFECTLY…..but that’s what hangs you up.

I’ve returned to skating several times after a several-month hiatus for various reasons, and my overthinking brain convinced me that, despite a quarter of a century of muscle memory and experience, I had to “think through” every aspect of certain moves.

But then I started ‘muscling’ certain simple jumps and spins, which wound them too tight, and I continued thinking that it was “hard” and that I had to overthink it to do it correctly.

It was only when I started thinking and TRYING less and letting my body do the skill that it started to be easy because I wasn’t making it needlessly complicated.

This is the kind of stuff that keeps sports psychologists busy. Athletes in every sport overthink the execution of specific skills, and this also happens in everyday life when pressure is on.

Some ways to counteract this are to let go of consciously thinking about executing a skill and just let your body do it (easier said than done). You can also find simple one-word mantras (focus moments) leading up to the movement. The idea is not to give yourself more excuses to overthink (and the brain loves to find justifications for doing that).

So when I go skating now, I think, “less thinking” or “let it go”. I realize now that the key to success is to try less and just let it happen.

Another thing I like to ask myself is, “Am I overcomplicating this?”

Because I am who I am, 95% of the time, that’s exactly what I’m doing, and that takes some of the pressure off so I can just get on with the practice and do what I already know how to do.

I’m focusing on building and making slow progress rather than putting too much pressure on myself to “compete” or achieve tangible goals

My ego has been driving the bus for the past several years. I thought the only way to be valuable as an adult skater was to do what other adult skaters did, which seemed to be competing in many competitions, taking skating tests, and racking up achievements. My goals were as follows:

Compete in the US Adult Championships elite class in 2025.

Compete in the International Figure Skating competition in Germany in the elite class in 2025.

Pass my Senior Free Skate test (finally) by summer 2025.

Get my double axel and at least one triple by fall 2025.

I realized I was setting my sights too high for my ability level and adding an (unnecessary) sense of urgency. I convinced myself that my time was running out. I’m 34, and although adult skating competitions have skaters in their 80s competing, if I wanted to compete in the elite class (against those doing doubles and sometimes triples), it would have to be sooner rather than later, while I could still do doubles. As I tend to do, I set a huge goal, started working hard, psyched myself out when I realized how far I had left to go, and then just gave up.

Then I got injured, which threw a definite wrench in my plans.

I realized I had to lower my expectations and take things one day at a time.

Now that I have new skates, I have put many of those goals into the future. My current goals are to break into my new skates, regain my skills, and allow my injury to heal fully.

Most importantly, I also permitted myself not to pursue those big goals if I didn’t want to.

Focusing on making a little progress every day and letting the chips fall where they may have helped me take the pressure off and enjoy my skating journey again.

2024 has been a year of discovery.

I’ve started questioning my patterns and ways of doing things and realized that, throughout my life, overthinking has made things more complicated than they need to be.

I realized I live primarily in my head (thanks, ADHD!), which sometimes leads to decision paralysis.

This also makes it difficult to fully live in my body, fully understand the process, and trust my feelings.

The only ways I could break out of these patterns were to force myself out of my comfort zone, think less, and do more while not trying too hard.

I consider these realizations considerable accomplishments in themselves, and I’m working on striking a balance between thinking, feeling, and doing this year.

This post has been edited from its original version on Medium.com.

As an also often overthinking perfectionist, I like that question "am I overcomplicating things?" Yes, the answer is always yes 😅